Climate Agreements and Global Action: A Series

“We affirm that no country will have to choose between fighting poverty and fighting for our planet.”

Thus was the declaration of the preamble to the G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration.

Hopeful? Yes.

Ambitious? Definitely.

Whether or not we can achieve this as a country is what we will be focusing on through this series on climate-driven inequities.

Also read: Multidimensional Poverty and its Predecessors

Where did it all begin?

It was in 1938 that an English steam engineer called Guy Callendar found a connection between the increase in carbon dioxide and the global warming phenomenon. After this, in 1956, Gilbert Plass created the Carbon Dioxide Theory of Climate Change, the paper for which can be found here. Essentially, the theory predicted that with the extra C02 released into the atmosphere through human industrial processes, the earth’s temperature would continue to rise, at least for several centuries.

Today, years after this theory, terms such as global warming, ozone layer depletion, melting glaciers, and, most significantly, climate change have become our reality. Natural disasters have become unnaturally frequent, and progress in the name of development has begun to be questioned for all the damage it eventually also ended up creating. All those renewable energy sources we read about as kids now also include the cons, which involve degrading aquatic life in water bodies that have dams for creating hydroelectricity, among a slew of other issues.

A history of global climate agreements has paved the way for nations to respond to climate change today. These agreements, created with hope for a better future, have had their share of failures and successes, which we will look at in this blog.

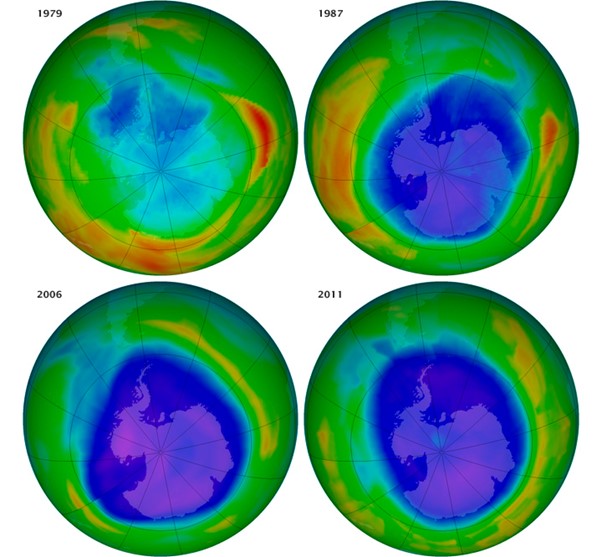

The Montreal Protocol, 1987

Created to tackle the depleting ozone layer in the stratosphere resulting from CFCs used in products like air conditioners, refrigerators, fire extinguishers, etc., this agreement eventually got all countries on board. Though not intended to deal with climate change directly, it was an international treaty that required all nations to take drastic steps to reduce the production of ozone-depleting substances to protect the stratosphere.

It has eliminated nearly 99% of these substances, restoring the ozone layer to its optimal level again.

The Montreal Protocol was an easier agreement because it only required some industries to innovate for a lower environmental impact. According to Durwood Zaelke, president of the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development, “Since the problem had been narrowed down to the fluorinated-gas universe, it allowed policymakers and scientists to learn faster and technology to develop faster”, which ended up happening. It also helped reduce 135 billion tons of C02-equivalent emissions as a cumulative effect.

This protocol also succeeded because it brought forth the Multilateral Fund, which held the developed nations responsible for providing financial assistance to developing countries so they could switch to greener chemicals.

The Convention, 1992

Formally known as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), this agreement has 197 countries explicitly signed to address climate change. The first of its kind, the Convention established an annual forum, known as the Conference of the Parties, or COP, for discussions among nations to stabilize the concentration of greenhouse gases.

This agreement also called for financial assistance from Parties with more financial resources to countries that need help and are more vulnerable to climate change.

The Paris Agreement, 2015

Building upon the Convention, the Paris Agreement brings together all nations into a common cause that displays ambitious efforts to combat climate change. It is a legally binding treaty that 196 countries have ratified to cut global greenhouse gas emissions.

The then Secretary General of the UN, Ban Ki-moon, said:

“The Paris Agreement provides a viable blueprint to mitigate the serious threats to our planet. It sets clear targets to restrict rising temperatures, limit greenhouse gas emissions, and facilitate climate-resilient development and green growth.”

Another crucial aspect of this agreement is that non-Party stakeholders, such as businesses and civil societies, were invited to begin contributions towards climate action.

Even under this Agreement, all countries are not treated the same way for obvious reasons. An inherent flexibility has allowed some countries to pledge net zero emissions by 2050, while other nations have set other goals. Most importantly, the agreement has put climate change in the public eye. The increasing internet connectivity has significantly contributed to the awareness around the issue. It has enabled individuals, businesses, and NGOs to become more climate-conscious in their day-to-day activities.

Together, these global climate agreements have led to a momentous shift in the urgency of mitigating climate change. Having achieved its goal, the Montreal Protocol has not been a one-and-done agreement. In fact, with amendments, the agreement has now started working on phasing out HFCs, hydrofluorocarbons, that are also harmful to the environment. The aim is to completely eliminate these by 2024, resulting in a 0.5-degree Celsius reduction in global warming this century. With the Paris Agreement, there have been significant strides in national and international commitments towards mitigating climate change. Still, the journey is not easy, which is what we will explore in the next blog.

References:

https://www.earthday.org/what-can-we-learn-from-the-montreal-protocol/

https://unfccc.int/blog/the-explainer-the-paris-agreement

Aishwarya Bhatia, Sambodhi