India’s Perplexing Gender Paradox

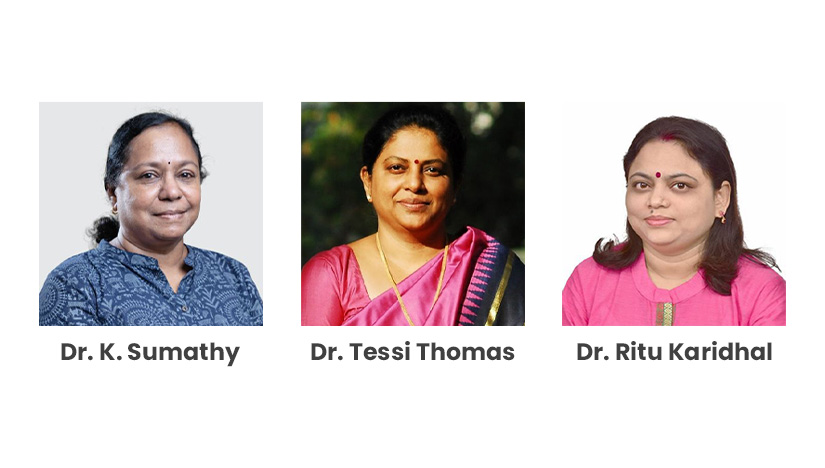

Some of the most significant scientific breakthroughs have come from Indian women scientists. Dr. K. Sumathy is the brain behind Covaxin, the first vaccine against COVID-19 from an Indian company. She was also instrumental in developing vaccines against Zika and Chikungunya. Dr. Tessi Thomas developed the Agni IV and V missiles and is popularly known as the ‘Missile Woman of India.’ Meanwhile, the ‘Rocket Woman of India’ is Dr. Ritu Karidhal, the artist behind the successful Mars Orbital Mission.

Yet, statistics reveal that despite having such role models in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields, many continue to believe such professions to be male-oriented.

A study found that 70% of individuals in 34 countries associated science more with males than with females. Moreover, there is gender bias in the curriculum, in expectations that parents, teachers, and peers have with individuals based on their gender.

There is also an inherent bias in access to different STEM resources. In India, more than 50% of illustrations in math and science textbooks for primary students depict boys and only 6% depict girls.

STEM is essential to a country’s economic and social prosperity, especially since it contributes immensely to achieving gender equality, the 5th SDG. However, the current picture shows how slow our progress has been in achieving this goal.

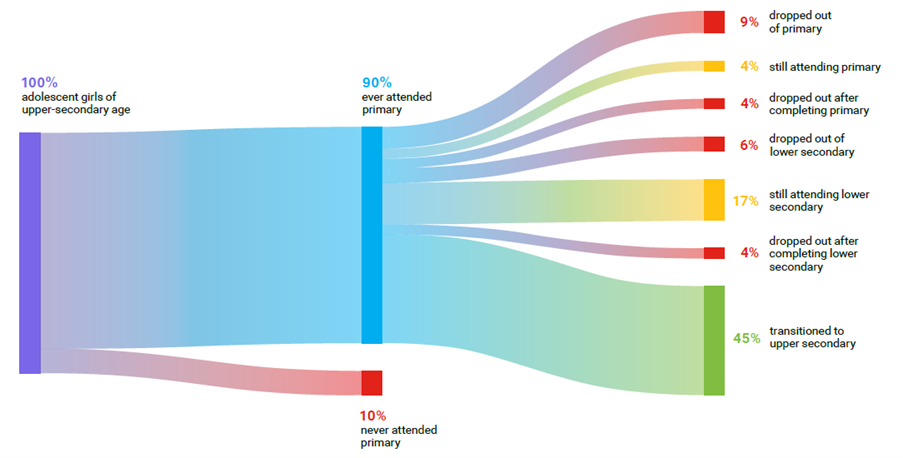

Research shows that while many adolescent girls begin primary education, fewer than half reach upper secondary level, where STEM skills can be further developed.

In India’s context, what’s even more interesting is the concept of the Gender Paradox.

According to a 2020 report by the United Nations, 43% of all graduates in STEM fields in India are women—the highest in the world. However, the report also found that only 14% of India’s STEM graduates employed in research institutes are women. The proportion of women among scientists in this country is much lower than the global proportion, which is 30%.

Moreover, despite the rising number of women STEM graduates, many qualified women scientists opt for undergraduate or school-level teaching assignments. In India, only 15-20% of faculty members hold tenured positions in research institutions and universities. Others drop entirely out of science, according to a report by an Indian policy think tank NITI Aayog.

Another report emphasizes that Indian women in STEM drop out of the workforce at critical phases in their lives, especially around childbearing years and, later, at mid-management levels.

We know the problem, but do we know the solution?

The answer is yes!

Global partnerships have helped generate mediums that can retain women in STEM careers. Some of them are listed below.

Forged by the UK in partnership with IISER Pune, this fund generates avenues to retain trained women workforce in science and empowers women candidates looking to transition into sectors that have the highest attrition rate, like STEM. It trained 370 women scientists to secure their retention in STEM through upskilling in professional avenues such as science administration & management, science journalism, and science policy.

The UK-India Education and Research Initiative (UKIERI) created this bilateral program between Bournville College of Further Education and the Confederation of Indian Industries to impart capacity-building exercises for Entrepreneurship Development to women from marginalized sections of society, such as survivors of domestic abuse and acid attacks. The purpose is to enable such survivors to earn a respectable living on their own. Till now, this partnership program has successfully engaged 359 women.

Let’s look at what India is doing to increase women’s participation in STEM.

The Gender Paradox is based on the steadily increasing representation of women among STEM graduates. Online learning platforms have also witnessed a surge in women applicants in STEM courses.

Despite this, only 15-20% of women in India are hired for tenured faculty positions in research institutions and universities. Despite the fact that STEM jobs in India are growing at a healthy rate, women remain underrepresented in STEM fields.

Working off these statistics, the Indian Government and institutions such as the Indian Academy of Sciences, The Indian National Science Academy, and the National Academy of Sciences India have undertaken several initiatives, some of which are as follows.

- Knowledge Involvement Research Advancement through Nurturing (KIRAN):

KIRAN addresses unemployment, career breaks, and relocation women scientists often face in their career trajectories.

More than 2200 women scientists and technologists have received fellowship support from the Women Scientist Scheme in the last five years to continue their education in science and technology. Under its mobility program, filler opportunities are provided to women scientists facing difficulties in their present job due to relocation and looking for alternative career options at their new location.

- The Indo-US Fellowship for Women in STEMM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics & Medicine)

Indian women who are scientists, engineers, or technologists can do international research with top institutions in the United States. This will help them improve their research skills.

It aims to strengthen women-only universities’ research and development (R&D) infrastructure. This has resulted in a significant increase in the number of quality publications in journals of repute by the faculty and researchers of beneficiary universities.

- Gender Advancement for Transforming Institutions (GATI):

Created by DST in collaboration with the British Council, GATI’s aims to transform institutions with a more gender-sensitive approach by fostering greater inclusivity in institutional systems and processes with the ultimate goal of improving gender equity. To achieve this end, a comprehensive charter and framework for assessing gender equity in STEM are being developed.

- Innovation in Science Pursuit for Inspired Research (INSPIRE):

This scheme enhances enrolment rates of young women in higher education, focusing on science-intensive programs.

For girls between the ages 17 and 22, the scheme provides scholarships and mentorship. Every year, it provides 1000 fellowships for a doctoral degree in both basic and applied sciences, such as engineering and medicine to women aged between 22 and 27 years. It also gives 1000 selected women post-doctoral researchers between the ages 27 and 32 the chance to work in both basic and applied sciences for five years in contractual and tenure-track positions.

This program is funded by DST and caters to meritorious girl students between the ages 15 and 18. It aims to create a level playing field by offering exposure to rural girl students in high school to help them plan their journey from school to college and further from research to a job of their choice in the field of science. The idea is to increase the participation of women in areas where they are under-represented within the larger domain of STEM.

- Indian Science Technology and Engineering facilities Map (I-STEM):

The I-STEM portal is an interactive portal for strengthening the R&D ecosystem in the country by providing access to information regarding research and employment opportunities for researchers, especially those coming from underserved communities.

In 2022, I-STEM launched a special drive for supporting Women in Engineering, Science, and Technology (WEST) through opportunities for skill enhancement. I-WhatsApp STEM’s and Telegram platforms have also been used to set up a digital consortium called “Connect Quickly” for online discussions and quick help.

The problem is known, and solutions also exist. What’s next?

Investment in solutions is the only way to ensure that such ideas are implemented to create the desired impact. Supporting infrastructure that helps women enter and sustain STEM careers is crucial to every intervention working to achieve its goals.

An excellent place to start would be breaking the gendered notions of intelligence and scientific and mathematical ability in schools, which will encourage more girls to take up science at the secondary and higher secondary level, as well as encourage them to envision a career in this domain. While the increasing number of women in STEM in India because of a supportive policy ecosystem is indicative of a positive change, we still have a long way to go in achieving the goal of equity.

Kaustav Ghosal – Deputy Research Manager, Sambodhi

Debapriya Chanda – Deputy Research Manager, Sambodhi