In 2021, India’s rural population crossed 900 million, which makes it larger than the entire population of Europe. India is projected to remain predominantly rural till 2050. Moreover, the rural economy constitutes 46% of the national income and 70% workforce. The last two decades have seen profound changes in India’s rural economy. As per the 1991 Census, 48.4% of the main workers in rural India were cultivators and 31.6% were agricultural labourers. By 2011, the census estimates that there are 40.3% cultivators and 32.9% agricultural labourers. This not only points to a significant shift in the agrarian base of our country but also hints at the fact that the shift has primarily gone to the secondary and tertiary sectors of the rural economy and not to wage Labour. Data shows that about two-thirds of rural income is now being generated in non-agricultural activities, and more than half of the value added in the manufacturing sector is being contributed by rural areas, but unfortunately, all without any significant employment gains.to the formal sector, which accounts for just about 10% of the workforce. For the balance majority, it is important for individuals to take control of their retirement planning and make decisions accordingly. It is often not appreciated enough that contributing to a pension arrangement can help one build up an extremely valuable asset.

Insights into Rural Entrepreneurship

Post the pandemic, the return of migrants to cities within a short time and a much lesser quantum of migration in the second wave showed limits of rural and transition habitats to provide productive engagement. In a scenario dominated by informal and fragile jobs, the poverty slide asks of the New Rural to become a productive habitat of human development, and social and economic mobility.

Today, the rural, peri-rural, and circular migrants are younger than ever, they are agile, aspirational, with higher school years, and with mobile and digital access. Rural areas today typify a highly diversified household economy that includes agriculture and allied sector, trading, and is heavily connected with urban/migration economy. But the fact of the matter is, there is growing unemployment, and opportunities haven’t grown in comparison. Government jobs have remained stagnant while the competition has soared, and the private sector hasn’t been able to create the number of jobs to absorb the remaining workers. While entrepreneurship promotion has grown over the years, this again is limited to urban technology start-ups while a large section of people is ignored in this process.

Entrepreneurship promotion in rural India tends to follow more of a ‘selfemployment’ promotion with a major focus on Own Account Enterprises. The approaches towards entrepreneurship are top-down that do not let the ecosystem emerge. In addition to this, the definitions used by the Ministry of MSMEs are too broad (and based on investment thresholds) and do not aptly capture the nano and mini businesses, making them visibly invisible.

In this line of thought, the key questions that require answers are

- Is the ecosystem being built that can support job creation and promote entrepreneurship?

- What are the aspirations of the people, especially adolescents and young adults?

- Are the entrepreneurs pursuing entrepreneurship only in subsistence/survival mode, or are they also creating more jobs?

- If we need to move towards job creation, what are the actors in the ecosystem that need to be udged/connected/unlocked?

In an attempt to answer some of these questions, a pan-national survey covering 2041 rural businesses was conducted by the Development Intelligence Unit with design inputs from Development Alternatives and using the pan-India panel established by SambodhiPanels. The survey also covered a total of 1906 adolescents and young adults aged between 16-29 years, exploring their attitudinal predispositions regarding entrepreneurship and their aspirations towards running their own businesses.

Some of the key highlights of the findings are as follows:

Within a village of 600 households, the average number of households where there was someone who was running a business enterprise was 6.3%. Nearly 62% of rural businesses are retail trading outlets. Nearly 9 out of 10 rural businesses are first-generation enterprises. This does not seem to be too many businesses running across rural India that are inter-generational.

Business economics

The median value of seed capital that has gone into these businesses is around Rs.50,000. The value is the same for retail businesses as well as non-retail. The premier source of finance for starting a business in rural India seems to be borrowing capital from friends and family/relations. About a quarter of the businesses were started with one’s own savings. Only one in five were started with bank loans.

The median value of expenses in running the business over the past six-month period stands at Rs.75,000. The median value of expenses for retail businesses is Rs.82,500 while that of non-retail businesses was Rs.50,000. Three out of four entrepreneurs solely used the revenue they made to keep their businesses running. About one in four also tapped their friends and relations for an infusion of capital. Instances of ever taking a financial institution loan in the last 6 months were only 14%..

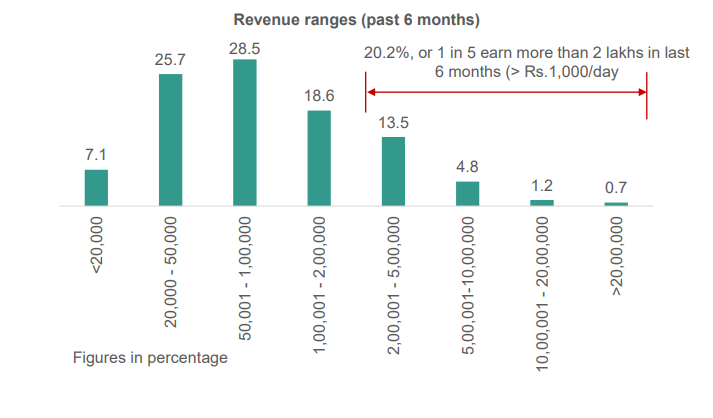

The median value of revenue of all types of enterprises over the past 6 months has been Rs.90,000. The revenue for retail businesses has been Rs.95,000 in the past 6 months (excluding inventory stock). For non-retail outlets, the revenue for the same period has been Rs.85,000. Similarly, the median value of revenue in the last six months for rural businesses that have at least one employee (full-time or part-time) has been Rs.1.50,000 while for businesses with no employees, it is Rs.70,000.

One in five rural businesses has earned revenue in excess of Rs. 2 lakhs in the last 6 months (greater than Rs.1,000/day. In comparison, the wage rate for skilled labour in Delhi, which is the highest in India, is Rs.783/day.